Cinque Terre

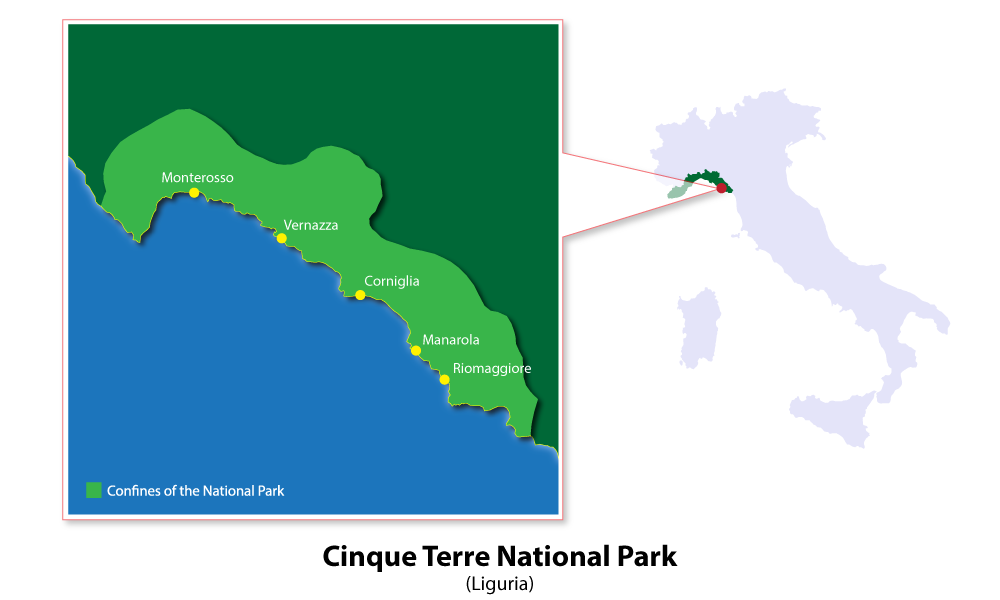

Cinque Terre is a small stretch of coastline just west of La Spezia in Liguria. It is named after five villages: Monterosso al Mare, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola and Riomaggiore.

It has a unique charm and was established as a National Park in 1999 and is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The villages are set on the steep hillside where cultivated terraces cascade down to the sea. No cars are allowed into the villages, but there is a local train that runs from La Spezia to Genoa that connects them. There is also a passenger ferry that runs between the five villages, except Corniglia. You can get the ferry from Genoa's Old Harbour, La Spezia, Lerici or Portovenere.

For more energetic visitors, there is a trail, known as the 'Sentiero Azzurro' (The Blue Trail), that connects the five villages. It is 10 kilometres long and the height difference is over 600 metres throughout its length. It takes approximately five hours to complete. The stretch between Riomaggiore and Manarola is called the 'Via Dell'Amore' (The road of love) and varies in difficulty from easy to extremely difficult. The stretch between Manarola to Corniglia is the easiest part, although the main trail into Corniglia does end in 368 steps. The trail between Corniglia and Vernazza is steep at certain places but the stretch between Vernazza and Monterosso is by far the steepest. It winds through olive orchards and vineyards and can get rough but walkers are rewarded with the best view of the bay and the spectacular views of both Monterosso and Vernazza.

Although the whole of the Cinque Terre is interesting and full of trails and excursions it is well worth taking time to examine each of the villages as a separate entity. They are all within the province of La Spezia and running from north to south they are:

Monterosso al Mare

Divided by a tunnel for pedestrians and cars (there are very few cars in this village) Monterosso is divided into two parts, the old town and the new town.

The beach is the only large sand beac in the whole of the Cinque Terre which makes it popular with tourists during the summer. Originally the village was only accessible either by boat or along one of the tiny mule tracks which have been maintained and are now used as hiking tracks. Monterosso al Mare is famous for its lemon trees which can be seen growing in profusion around the whole area. There is a partially ruined Genoese castle and the Convent of Monterosso al Mare which has many historical treasures within its interior. The church of St. John the baptist has four marble columns and a square, medieval bell tower with four merlons on top.

Vernazza

Little has changed in Vernazza which was, and still is, a small fishing village with no cars. This village is considered to be the most beautiful of the five, if not one of the most beautiful in Italy.

In the past it had constant problems with pirates and in the 15th century it built a fortified wall to help them in their defence against the onslaughts. Later in history they terraced the land and planted vineyards creating a successful wine industry. In 2011, on October 25th, Vernazza was hit by torrential rain which caused extensive flooding and mudslides which left the village buried under four metres of mud and rubble. The village had to be evacuated and was classed as a state of emergency with over one million euros worth of damage. After a lot of hard work is now almost restored, the people have returned, businesses have reopened and it is once again ready to receive visitors.

Corniglia

This is the only one of the five which is not directly next to the sea but is perched on a promontory which is around 100 metres high.

One side is excessively steep and drops straight down to the sea, the other three sides are terraced and covered in vineyards. To access the village without a car you must climb up 382 steps or wind your way up the narrow road leading from the station. There is a bus which runs sporadically from the station to the village. Corniglia has narrow streets, the main one being Fieschi along which all the houses of the village run. One side of every house faces this road and the other side faces the sea. There is a small terrace in the rock from where it is possible to see the other four villages, Monterosso al Mare and Vernazza on one side and Manarola and Riomaggiore on the other.

Manarola

Built on a rock 70 metres high Mararola is the second smallest of the five villages and also the oldest.

The local church, San Lorenzo, has a cornerstone dated 1338. Although the village is above sea level, unlike Corniglia, it does have direct sea access although not a proper beach. It does however have very clean, clear and deep water making it an excellent place for swimming. It is a charming village with narrow streets and pretty multi-coloured houses all facing the sea. It is a fishing village and is also famous for its production of wine, in particular a wine called Sciacchetrà.

Riomaggiore

The southernmost of the five, Riomaggiore is also the largest and the unofficial headquarters of the Cinque Terre with the office of the National Park being based there.

It has tall, multi-coloured houses with slate rooves lining steep, narrow roads interconnected by steps. Riomaggiore is pretty by day but when it is lit up at night it appears even prettier. It is also, due to its position, renowned for its beautiful sunsets.

A short video to support this article.