Spartacus

The name Spartacus resonates through history as a symbol of resistance, freedom, and defiance against tyranny. Once a Thracian warrior turned gladiator, Spartacus led one of the most extraordinary slave revolts in ancient history, the Third Servile War, against the mighty Roman Republic. His rebellion shook the foundations of Rome and captured the imagination of generations to come, from ancient historians to modern revolutionaries.

Early Life: From Thrace to the Arena

Little is definitively known about Spartacus's early life, but ancient sources agree he was born in Thrace (in modern-day Bulgaria or northeastern Greece) around 111 BC. Thrace was a region known for its fierce warriors, and Spartacus likely served as a soldier in the Roman auxiliary forces before deserting or rebelling.

Captured by the Romans, Spartacus was enslaved and sent to the gladiator training school (ludus) in Capua, run by Lentulus Batiatus. There, he was trained to fight in the arena for the entertainment of Roman crowds, a brutal life where death was a daily spectacle.

The Spark of Rebellion

In 73 BC, Spartacus and approximately 70–80 fellow gladiators orchestrated a daring escape from the Capuan school. Armed initially with kitchen tools and makeshift weapons, they fought their way to freedom and captured proper arms from traveling caravans and local Roman forces.

They fled to the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, using the natural terrain as a defensive stronghold. Word of their rebellion spread rapidly. Thousands of slaves, herdsmen, and disenfranchised peasants flocked to join them. The small band grew into a powerful rebel army, reportedly reaching over 70,000 men at its peak.

The Third Servile War Begins

Rome initially underestimated the rebels. Early Roman forces sent to crush the uprising were defeated repeatedly. Spartacus proved to be a brilliant and adaptable commander. He used guerrilla tactics, surprise attacks, and deep knowledge of terrain to humiliate Roman legions.

His army roamed southern Italy for nearly two years, defeating consuls and generals, including Claudius Glaber and Publius Varinius. Spartacus didn’t just seek vengeance, he aimed for freedom. His early goal appears to have been to escape Italy, possibly through the Alps, allowing his followers to return to their homelands.

However, internal divisions among the rebels and the lure of plunder caused the army to change direction multiple times, which ultimately contributed to their downfall.

Spartacus the Strategist

Despite being labeled a mere gladiator by Roman elites, Spartacus demonstrated exceptional military skill. He organized and supplied a vast and diverse force, creating a quasi-military structure among former slaves, gladiators, and others who had never before held arms.

He also showed a level of discipline and restraint, he is said to have punished looters and tried to prevent unnecessary cruelty. In some accounts, he even refused to be called king, although others claim he accepted a symbolic leadership role as the rebellion's figurehead.

Rome Responds: Crassus Takes Command

By 71 BC, Rome could no longer tolerate the humiliation. The Senate gave Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the richest men in Rome, command of eight legions, around 40,000 to 50,000 soldiers, and charged him with putting down the rebellion.

Crassus used harsh discipline, including decimation (executing one in every ten men for cowardice), to restore Roman morale. He also built massive fortifications across the Isthmus of Rhegium, trapping Spartacus in the southern tip of Italy.

Though Spartacus made one last desperate attempt to escape northward, his army was fragmented and exhausted.

The Final Battle and Death of Spartacus

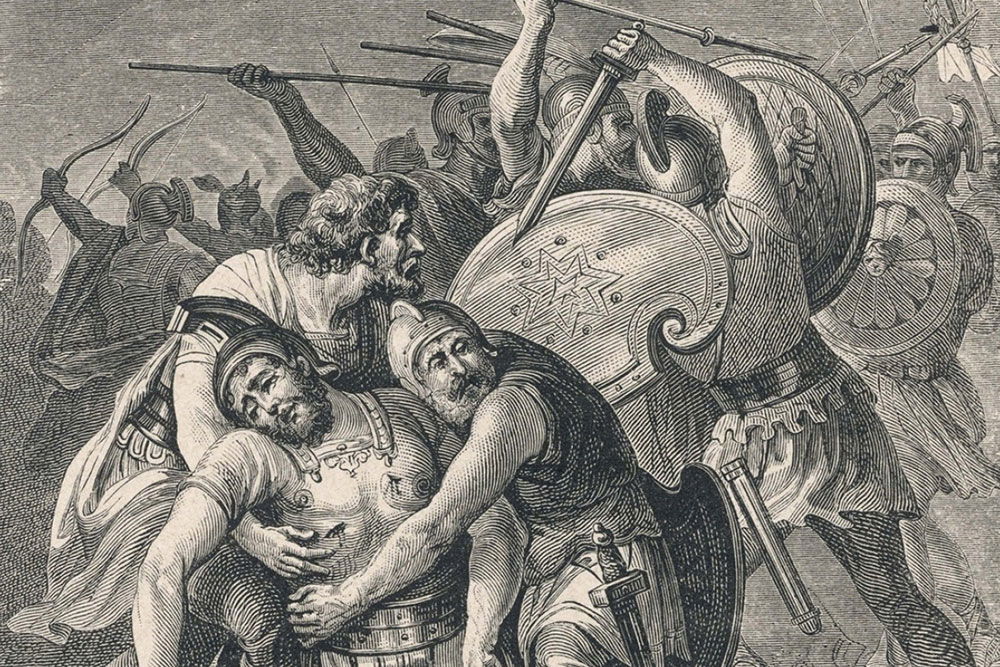

The final confrontation came in 71 BC in Lucania, in southern Italy. Spartacus and his men fought valiantly, but they were ultimately overwhelmed by Crassus’s superior forces.

Spartacus is believed to have died in battle, though his body was never found. He reportedly fought at the front lines, trying to reach Crassus himself in single combat. His death marked the collapse of the slave uprising.

Around 6,000 captured rebels were crucified along the Appian Way between Rome and Capua, a grim reminder of Roman retribution.

Legacy of Spartacus

Though the revolt failed, Spartacus became a lasting symbol of courage, defiance, and the universal human yearning for freedom. Ancient Roman historians, including Plutarch, Appian, and Florus, wrote of him with a mixture of fear and admiration.

In later centuries, Spartacus’s legend was revived by Karl Marx, who hailed him as a true hero of the oppressed. His story inspired literature, art, film, and revolutionary movements. The 1960 film *Spartacus*, starring Kirk Douglas, introduced his legend to a global audience, immortalizing the famous line: “I am Spartacus!”

Conclusion

Spartacus was more than a gladiator; he was a visionary leader who dared to defy one of the most powerful empires in history. His rebellion exposed the cracks in Rome’s social system and the dangers of building an economy on the backs of enslaved people.

Though crushed militarily, Spartacus triumphed morally and symbolically. His fight for freedom and justice still echoes today, reminding us that even in the darkest times, resistance is possible, and the human spirit cannot be easily broken.