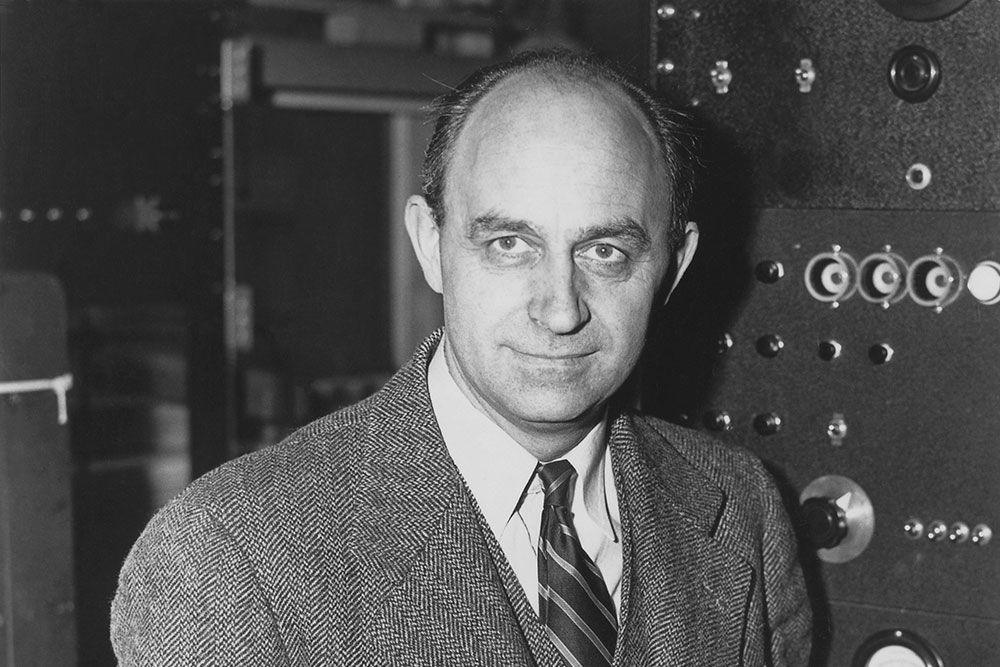

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi, one of the most brilliant physicists of the 20th century, made groundbreaking contributions to nuclear physics, quantum mechanics, and statistical mechanics. His pioneering work led to the development of the first nuclear reactor, and his theories paved the way for nuclear energy and the atomic bomb. Fermi's scientific achievements not only shaped modern physics but also had a profound impact on global history.

Early Life and Education

Enrico Fermi was born on September 29, 1901, in Rome, Italy. From an early age, he displayed an exceptional talent for mathematics and physics. As a child, he constructed mechanical devices, studied advanced textbooks, and showed a deep curiosity about the natural world. Encouraged by his father and a family friend, he pursued higher education at the prestigious Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa.

In 1922, at just 21 years old, Fermi earned his doctorate in physics. His thesis focused on X-ray diffraction and crystallography, showcasing his early interest in experimental physics. He then traveled to Göttingen, Germany, and Leiden, Netherlands, to work with some of the greatest minds in theoretical physics, including Max Born and Paul Ehrenfest.

Fermi’s Contributions to Quantum Mechanics and Statistical Physics

Fermi's first major contribution to physics was in statistical mechanics. In 1926, he developed what is now known as Fermi-Dirac statistics, independently of British physicist Paul Dirac. This theory describes the behavior of fermions, a class of subatomic particles (such as electrons, protons, and neutrons) that follow the Pauli exclusion principle, meaning no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously.

This discovery was crucial for understanding the structure of atoms and the behavior of electrons in metals, leading to advancements in semiconductors and quantum mechanics. Today, "fermions" are named in Fermi’s honour.

The Discovery of Neutron-Induced Radioactivity

In the early 1930s, Fermi turned his attention to nuclear physics, an emerging field at the time. He hypothesized that bombarding elements with neutrons could create radioactive isotopes. This work, conducted in Rome with a group of talented physicists known as the "Via Panisperna Boys," led to the discovery of neutron-induced radioactivity.

His experiments with slow neutrons, neutrons moving at reduced speeds, were particularly groundbreaking. He found that slow neutrons were more likely to be absorbed by atomic nuclei, a crucial insight that later enabled nuclear fission.

In 1938, Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on neutron-induced reactions. However, by this time, the political climate in Italy had changed under Mussolini’s fascist regime, and Fermi, whose wife was Jewish, decided to use his trip to Stockholm for the Nobel ceremony as an opportunity to escape. Instead of returning to Italy, he moved his family to the United States.

The Birth of Nuclear Power and the Atomic Bomb

Upon arriving in the U.S., Fermi joined Columbia University, where he and his team continued their nuclear research. His experiments confirmed that when uranium was bombarded with slow neutrons, it underwent fission, splitting into smaller nuclei and releasing enormous amounts of energy.

Recognizing the military and scientific implications of nuclear fission, Fermi became a key figure in the Manhattan Project, the secret U.S. program to develop an atomic bomb during World War II. In 1942, at the University of Chicago, Fermi and his team successfully built and operated the world's first controlled nuclear reactor, known as Chicago Pile-1. This experiment, conducted beneath the stands of an abandoned football stadium, proved that a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was possible.

The success of this experiment laid the foundation for nuclear energy and weapons. Fermi’s work directly contributed to the development of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Although he played a critical role in the project, Fermi was deeply concerned about the ethical implications of nuclear weapons and later advocated for arms control.

Fermi’s Later Work and Contributions to Astrophysics

After World War II, Fermi continued his research at the University of Chicago, focusing on high-energy physics, particle physics, and cosmology. He studied cosmic rays and proposed theories about the origin of high-energy particles in space. His work led to the development of the Fermi Paradox, a thought experiment questioning why, given the vast number of potentially habitable planets, humanity has not yet encountered extraterrestrial life.

He also played a key role in the development of early particle accelerators and theoretical models that predicted the existence of neutrinos, ghostly particles that interact only weakly with matter. His legacy in physics continued to grow, influencing generations of scientists.

Death and Legacy

In 1954, Enrico Fermi was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He passed away on November 28, 1954, at the age of 53. Despite his relatively short life, his contributions to science were immense, and his work continues to influence modern physics, energy production, and space exploration.

Honors and Recognitions

Fermi’s name is forever linked to some of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Several institutions, theories, and scientific terms have been named in his honor, including:

- Fermilab, the U.S. particle physics laboratory in Illinois

- Fermium (Fm), the chemical element with atomic number 100

- The Fermi Paradox, questioning why we haven’t found extraterrestrial life

- Fermi-Dirac statistics, fundamental in quantum mechanics

- The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, used to study cosmic phenomena

Conclusion: A Scientific Giant

Enrico Fermi’s genius extended across multiple disciplines, from nuclear physics to quantum mechanics and astrophysics. His discoveries paved the way for the development of nuclear power, modern electronics, and space exploration. As one of the most influential scientists in history, his work continues to inspire physicists and engineers worldwide.

His legacy is a testament to the power of human curiosity, the pursuit of knowledge, and the ethical responsibility of scientific discovery. Whether in the realm of atomic energy, particle physics, or the search for extraterrestrial life, Enrico Fermi’s influence will be felt for generations to come.